All we know of Wace is to be found within his poems. The preceding excerpt from the Roman de Rou, representing almost all the biographical details available, was written near the close of his career when he may have wished to leave behind more than a record of only other people's lives. Wace wove his own life into the poem, unfortunately omitting his birthdate, which, scholars speculate, falls between 1090 and 1110, with 1100 being the date commonly accepted.

The name "Wace" or "Guace" possibly comes from the Teutonic Wazo, an older form of the modern French Gace or Gasse, or as some would have it, the vernacular form of Eustache. Wace appears to have had no other name, single names being a not-uncommon occurrence in the twelfth century; before the reign of Henry II, surnames were rare though not unknown. There have been persistent attempts to tack on a Christian name, whether Robert, Richard, or Matthieu. As a name, "Wace" is recorded as being in use in Jersey until the end of the 16th Century.

Wace's ancestry may or may not have been humble: some sources think he was of "noble race," his mother the daughter of Toustein, chamberlain to Robert I of Normandy. Or Wace may have been the son of a carpenter who helped to construct the fleet for the Norman Conquest, or who knew those who had participated and passed on their recollections to his son. From his boyhood on an island, Wace gained first-hand knowledge of the sea and sea-going craft, which he put to good use later in detailed maritime descriptions.

The firmest evidence for upper class lineage lies with the fact of his being sent away to be educated: as a child, Wace was sent to Caen in Normandy to learn Latin ("a letres mis"). The farmers and fishermen who composed the population of Jersey could not have aspired to higher education except by seeking to enter the priesthood. If Wace had come from a seigneurial family, there would be reason to expect some record of that fact, and the threat of poverty that hung over his head throughout his lifetime would have been diminished. A background as a member of the petty nobility, with a respect for education and the need to make a living, might best describe his circumstances.

Around 1130 Wace returned to Caen and became clerc lisant, an ecclesiatical position with unspecified duties generally thought to have included writing, composing, and reading aloud. "To read" in the Middle Ages meant to teach publicly; a maistre lisant would indicate an authoritative teacher. In the Latin of the charters, teachers were indicated as "magister" or "magister scholarum". Wace, it may be supposed, was a clerc lisant who became a maistre lisant, the Maistre Wace who names himself fifteen times in his writings, proudly using the designation "maistre" ten times to indicate that he was a professional man, proud of his occupation and of his standing within it. In fact, he was a man of many overlapping professions: teacher, translator, historian, poet, canon - evidently winning the respect of his peers in each of these fields.

(From "Wace: His Literary Legacy" by Marleen Hacquoil)

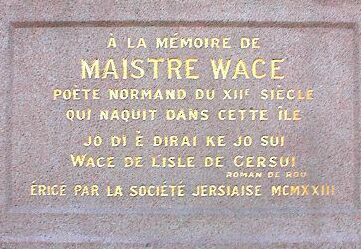

The plaque in the Royal Square commemorates Jersey's first known writer, the 12th century Norman poet Wace, author of the Roman de Rou, a history of the Norman people. Other than the fact that he was born in the Island, nothing is known about his life here, not even his birth date, but his influence on both French and British literature has been profound.

JEP 9/10/2003

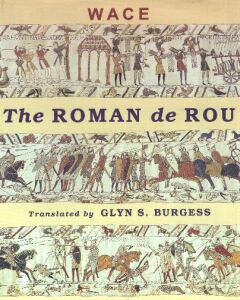

The first English translation of an epic poem by Jersey's most eminent writer, Maître Wace, was launched on Monday in the members' room at the Société Jersiaise.

Wace, who was born in the Island but spent much of his life in Normandy, wrote the 17,000-line Roman de Rou for King Henry II of England in the 12th century, but it was not until four years ago that an English version of the work began to take shape.

The long and painstaking task of translating Wace's Old French account of the Dukes of Normandy, the Battle of Hastings and the rise of the Norman kings of England was undertaken by Professor Glyn Burgess, the head of the French department at the University of Liverpool.

However, the project was initiated by the Société as one of its projects to mark the beginning of the new millennium and it was overseen by publications committee chairman Roger Long.

At the launch, the Bailiff, Sir Philip Bailhache, who wrote the translation's foreword, said that if the English have Shakespeare, Germany Goethe, and France Molière, Jersey can be proud to say that Wace is its literary hero.

Describing the poet as 'un vrai jèrriais', Sir Philip also said that he had formed the impression that Wace was more interested in the truth than in propaganda.

That, he explained, was a Jersey characteristic, adding: 'The Jerseyman has great respect for royalty and is loyal as any subject is likely to be. But he is not going to kowtow to the king, because he knows that in a sense he is as good as the king.'

Introducing the translator, who travelled to the Island for the ceremony, Sir Philip, said: 'This is a marvellous publication and we owe a great debt of gratitude to Professor Burgess.'

Calling the Roman de Rou 'his baby', the professor said that the process of translation had given new meaning to the saying 'art is long but life is brief'.

He also paid tribute to Elisabeth Van Houts, who supplied extensive historical notes to complement the text, and to Anthony Holden, whose version of the manuscript provided the raw material for translation.

Earlier, Roger Long had explained that he had managed to persuade the contractors working on the States building to remove the scaffolding which has concealed the Wace plaque for many months.

This, he explained, would enable Lionel Wace, a member of an organisation called the Writers' Alliance for Cultural Education - WACE - who travelled from Canada for yesterday's event, to view the Island's memorial to its foremost poet at first hand.

In common with other members of WACE, Mr Wace takes a deep interest in the poet and suspects that he might even be a descendant.

Mr Long, who likes to describe Maître Wace as a 'local author', also stressed that Professor Burgess's translation is not merely a work of local interest but one of international literary and historical significance.

JEP 14/5/2002

Linguists will tell you that Jèrriais is a Romance language, that it is derived from the langue d'oïl, that it is of western Norman origin and that it is full of words of Norse derivation.

Historians will tell you that it is quite close to the language of William the Conqueror and of the poet Maistre Wace, the Jersey-born author of 'Roman de Rou'.

Jersey Evening Post 4/1/2000

The works of the mediaeval Jersey poet Maistre Wace, notably 'Le Roman de Rou' (which has been called the first epic in modern European literature), contributed to the development of literary French, but the first known modern work in Jèrriais was penned in 1795 by Matthieu Le Geyt, who wrote some lines praising the beneficial effect of tobacco.

JEP 29/9/1998

Within the past few days I received the 1946 Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica... Our literary life receives short shrift. "The old Norman French patois is dying out. None of the dialects has received much literary cultivation. Jersey was the birthplace of the Norman poet (Wace) in the 12th century."

Morning News 8/1/1947

The local patois is the tongue of Wace, the Jerseyman who became the national poet of Normandy....

Times (London) 9/8/1944

None of the dialects have received much literary cultivation, though Jersey is proud of being the birthplace of one of the principal Norman poets, R. Wace, and has given a number of writers to English literature.

Encyclopaedia Britannica

1876

La langue des troubadours, la langue d'oc est cultivée comme langue morte dans le midi de la France, pourquoi notre idiôme illustré par Robert Wace et par les trouvères serait-il abandonné par nous? La langue française ne doit-elle pas beaucoup plus à l'un qu'à l'autre de ces dérivés du latin?

La Tribune de Jersey

Novembre 1860

Seven hundred years ago, a child born in Jersey was sent to study at Caen. This child gave such manifest indications of genius that the Church attached him to themselves, and Henry II., King of England and Duke of Normandy, gave him a prebend's stall in the cathedral of Bayeux. This young ecclesiastic was Robert Vace, the first Norman trouvere and the first French poet:

Je di e dirai ke je sui

Vaice de l'isle de Gersui.

And this Vaice of the Isle of Gersui sang the "Conquest of Neustria by the Men of the North," the "Odyssey of Rollo," and penned the great national epic, the "Conquest of England by the Normans." The language used by Robert Vace was called "la langue d'oil;" it was the language of the North and that of Rome fused together — the work of three centuries. The first who ventured to write in it was this peasant of Jersey.

The New Monthly Magazine, 1858

La langue Normande a enfin nos sympathies. Nous tenons, nous aussi, à cette langue - cette langue que parlèrent nos pères, doit être aussi la nôtre. Peut-être qu'elle n'est pas si élégante que celle de la mère patrie, cependant elle nous rappelle notre origine, et nous est par cela même chère. Elle nous rappelle le poéte Wace du XIIe siècle, qui chanta en cette langue la Normandie et les exploits de ses anciens ducs, dont les ouvrages, après avoir été peu connus pendant des siècles, ont acquis de la publicité et de la renommée par le moyen d'une presse Normande. Tâchons de conserver notre langue, ou comme quelques-uns l'appellent, notre Patois.

La Patrie

19/10/1850

The word " pure" may be thought by some, to be inappropriately used; but in fact, the patois of both islands, as it is spoken in the interior parishes, is nearly the pure French of some centuries ago; and while the French has changed, the language of these Norman islands remains nearly as when Wace, the Jersey poet, composed his " Roman du Rou," in the year 1160.

The Channel Islands

Henry D. Inglis

1835