Ladies and gentlemen, for those of you who are looking worried, please don't fear - I do not intend to deliver the whole of my fifteen minutes in Jèrriais (known in English as Jersey Norman-French or less correctly as Jersey-French) The extraordinary thing is that what you have heard in the last moments is probably all that you would hear spoken during a holiday in Jersey - unless you were very fortunate, and that is despite the fact that it is our island's own language.

I intend to give you a brief linguistic history of our island followed by some details of our programme for the teaching of Jèrriais.

Jersey has been in the throes of a language shift over at least the past two hundred years, which has threatened to lead to the death of Jèrriais. The island has moved from being a rural, mostly Francophone community to a very affluent, hi-tech almost exclusively English-speaking one (with the exception of the immigrant workers - one tenth of our population today is of Portuguese origin).

Language shift is nothing new. The tribes which built the dolmens after Jersey became an island around 7000 years ago were probably Celtic speakers.

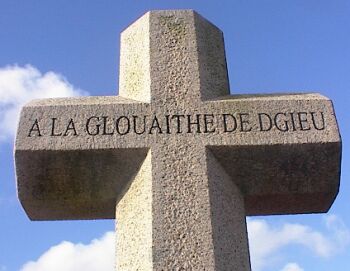

Despite the comings and goings of Kings and invaders in Mainland Gaul, it is probable that Celtic would have been the means of communication used by inhabitants, traders, visitors and missionaries in Jersey. Christainity arrived in the 6th Century, brought by Missionaries including St. Samson, St. Marcoulf, St. Malo and St. Helier. We know that in the eighth and ninth centuries, Jersey, known at the time as Angia, became part of an autonomous Brittany, under the rule of the Breton king.

Despite the comings and goings of Kings and invaders in Mainland Gaul, it is probable that Celtic would have been the means of communication used by inhabitants, traders, visitors and missionaries in Jersey. Christainity arrived in the 6th Century, brought by Missionaries including St. Samson, St. Marcoulf, St. Malo and St. Helier. We know that in the eighth and ninth centuries, Jersey, known at the time as Angia, became part of an autonomous Brittany, under the rule of the Breton king. However this situation did not last long, as from the ninth century, a period of settlement by the Vikings began. Viking raids in the province of Neustria led to the establishment by treaty of the duchy of Normandy notionally under the French king. The Norse leader, Rolf the Ganger became Rollo, the first Duke of Normandy.

Rollo's successors proved to be able rulers, and adopted the Gallo-Romance language of the country flavoured with words and sounds from their native Norse, which remains evident in Jèrriais today. However, by the eleventh century, land resources were running dangerously low, and the pressure to expand was becoming explosive. It was a question of conquest or going under. So it was that Duke William the Bastard led his aristocracy from all over the duchy in the greatest military operation of the era - and so Jersey-men can justifiably claim to have been on the winning side at Hastings, so England belongs to us and not the other way round! And our duke, William the Bastard is now better known as William the Conqueror.

Normandy, probably including the islands, was conquered by the increasingly-powerful French around 1204 but the islands were recovered very soon afterwards - King John and his advisers saw that they provided him with a foothold in the Duchy of Normandy to support his (tenuous) legal claims on the whole territory, a base for a military recovery which never happened and a safe stopping-point on the sea-route from Gascony to England. The Channel Islands remained faithful to the crown and became frontier outposts for Britain.

During the first six centuries of rule by the English crown, the island's geographical isolation from the British mainland and its regular contact with Normandy, despite the restrictions which the authorities tried to place on it, ensured that Jèrriais and French were the dominant languages, with English being a much more rarely used medium. Up till the Reformation, the Channel Islands fell within the Diocese of Coutances in Normandy. Most of the population remained unfamiliar with English up till the Napoleonic wars.

An abortive French invasion in 1781 ended in their defeat at the Battle of Jersey, the last battle to be fought on British soil. From 1793 to 1815, the French military eyed the islands as possible additions to the Empire, and as a result, a large British garrison was stationed in Jersey. A massive military building programme involving a mainly English-speaking workforce strengthened the island's defences.

Following the decline of the French threat, a large body of British immigrants arrived - attracted by both the climate and the fact that the cost of living here was considerably cheaper than in England, the reverse of the present day. These immigrants were convinced of the superiority of the language of the British Empire and they were certainly not going to learn the local tongue.

A 19th Century writer said that the future economic prosperity and general happiness of Jersey was linked with the need for a thorough anglicisation of the island. He was however rather premature in his estimate that Jersey would see a complete acceptance of English by 1850. When Queen Victoria visited in 1846 and expressed her approval of the language which she thought sounded like Welsh, her escort, Colonel John Le Couteur of the parish of St. Brelade was quick to point out that while Jèrriais might be the language of the people, there were English schools in every parish. Jean Sullivan, a Jèrriais author, warned of the danger of following in the footsteps of Cornish, suggesting that education in Jèrriais as well as French was the only way of preventing the language from disappearing - sadly no-one paid any attention until a century after his death!

A 19th Century writer said that the future economic prosperity and general happiness of Jersey was linked with the need for a thorough anglicisation of the island. He was however rather premature in his estimate that Jersey would see a complete acceptance of English by 1850. When Queen Victoria visited in 1846 and expressed her approval of the language which she thought sounded like Welsh, her escort, Colonel John Le Couteur of the parish of St. Brelade was quick to point out that while Jèrriais might be the language of the people, there were English schools in every parish. Jean Sullivan, a Jèrriais author, warned of the danger of following in the footsteps of Cornish, suggesting that education in Jèrriais as well as French was the only way of preventing the language from disappearing - sadly no-one paid any attention until a century after his death! The big problem for Jèrriais came with the introduction of compulsory education. Children went to school where both English and French were foreign languages and had to be rapidly learnt.

In the twentieth century, change continued apace. Children were actively discouraged from speaking their own language and punishments were administered for those caught doing so. Under increasing social pressure, family and place names were anglicised - Le Hegerat being changed to Garrett, La Grande Charriere becoming Millards' Corner, the family owned store Voisin being mis-pronounced Voysins. Jèrriais and French were becoming less and less used.

The final flowering as well as the biggest blow to the survival of the language was the German occupation in 1940 and the evacuation of 30% of the population - including more than 1000 out of the island's 5500 schoolchildren. Jèrriais was used by some of those who remained behind as a secret language, incomprehensible to the invaders. The Germans even brought in interpreters from Paris, who were equally unable to understand the spoken language.

In 1945 the returning evacuees, having experienced five years of British education, many now speaking with Yorkshire or Scottish accents, saw little need to keep the language alive. According to the 1989 census, the first to ask questions on language, only 5720 people out of a population of 82,000 spoke Jèrriais. By 2001 this had dropped to just over 2,700 or 3.18%.

The population balance has shifted too - now over 50% of residents are not locally born, and many of those who come to work in Jersey have no interest in the traditions of the island - the finance industry which brings us so much wealth sucks in people who view their working life in the island as an extended holiday.

However, for Jèrriais there is more hope now than for many years. The falling numbers of speakers had been long recognised, and it was also evident that transmission within the family was declining; indeed most speakers were no longer of childbearing age (by 2001 the biggest group of speakers ranked by age was that between 70 and 74 years old)

The language had been taught to adults at evening classes since the 1960s, I myself, a bougre d'Angliais (which I will translate as “an English person!”) having been an evening class student from the early 1980s, but it was recognised that this could not in itself maintain the dwindling number of speakers. In 1997, I was one of a group who brought the revival programme for Manx to the attention of a senior politician, Senator Jean Le Maistre, and he persuaded the President of the Education Committee to support a survey of parents of primary-school children to find out what the likely demand for Jèrriais lessons might be. Their best estimate of the result was that there might be 100 parents interested, so they were amazed by the response - some 780 families wanting their children to have the chance to learn the language. As a result, the States of Jersey funded a two-year trial, for which I was fortunate to be appointed co-ordinator, to be administered jointly by the Education Service and Le Don Balleine, a trust which had been involved in publishing Jèrriais works since the 1950s.

I decided at the outset not to model the Jèrriais programme on the established French course, in order to avoid any possibility of accusations of cross-contamination which might have resulted from the similarity of the two languages; instead I contacted Dr. Brian Stowell in the Isle of Man, who kindly allowed me to use the Manx example as a pattern, despite the lack of linguistic relationship. I even picked up a smattering of Manx while working on the translation of the first two textbooks! The Manx connection has continued ever since, and has proved very beneficial to me and my teaching team - and I think that they have had value from it too. It has to be remembered that because we are both outside the EU we cannot have access to regional minority language funding, or participate in programmes like Comenius and I was warned to avoid any involvement that might cause the island political embarrassment. However we are both members of CAER, the Welsh acronym for The Language Society of the European Regions, which permits us to get valuable cross-feed from other minority language areas, and my office subscribes to the Foundation for Endangered Languages. It is worth mentioning also that the French constitutional council has outlawed teaching in regional languages, including mainland Norman, and has blocked the ratification of the European Convention of Regional and Minority Languages. We therefore have no opposite numbers with which to work in mainland Normandy.

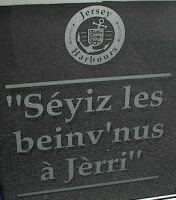

I decided at the outset not to model the Jèrriais programme on the established French course, in order to avoid any possibility of accusations of cross-contamination which might have resulted from the similarity of the two languages; instead I contacted Dr. Brian Stowell in the Isle of Man, who kindly allowed me to use the Manx example as a pattern, despite the lack of linguistic relationship. I even picked up a smattering of Manx while working on the translation of the first two textbooks! The Manx connection has continued ever since, and has proved very beneficial to me and my teaching team - and I think that they have had value from it too. It has to be remembered that because we are both outside the EU we cannot have access to regional minority language funding, or participate in programmes like Comenius and I was warned to avoid any involvement that might cause the island political embarrassment. However we are both members of CAER, the Welsh acronym for The Language Society of the European Regions, which permits us to get valuable cross-feed from other minority language areas, and my office subscribes to the Foundation for Endangered Languages. It is worth mentioning also that the French constitutional council has outlawed teaching in regional languages, including mainland Norman, and has blocked the ratification of the European Convention of Regional and Minority Languages. We therefore have no opposite numbers with which to work in mainland Normandy.I ran a trial of the first textbook and other material in one primary school in Spring 1999, and launched the full programme in September of that year. Children who volunteered to take part were offered a 30 minute lesson once a week on an extra-curricular basis; not all schools took part in the programme, but those that did were very supportive and children were generally enthusiastic about learning “their own” language - we even noticed a spill-over with children who have never attended our classes calling “bouanjour” or “à bétôt” to members of the teaching team.

Following on from the success of the trial, we were voted increased funding for the five years ending 2005. This enabled us to move the programme forward and to follow the children who had already started learning Jèrriais into secondary schools; however it has to be said that the numbers fall off alarmingly during the transition, something which we are addressing at present. It has been suggested that one way to improve the secondary take-up might be to introduce a qualification in Jèrriais - a Certificate of Achievement or GCSE equivalent, but we are still faced with the fact that we only have thirty minutes per week to teach our pupils the language.

Following on from the success of the trial, we were voted increased funding for the five years ending 2005. This enabled us to move the programme forward and to follow the children who had already started learning Jèrriais into secondary schools; however it has to be said that the numbers fall off alarmingly during the transition, something which we are addressing at present. It has been suggested that one way to improve the secondary take-up might be to introduce a qualification in Jèrriais - a Certificate of Achievement or GCSE equivalent, but we are still faced with the fact that we only have thirty minutes per week to teach our pupils the language.Until last year we introduced children to Jèrriais in Year 5, as in almost all schools they began to learn French in Year 4, which gave us the advantage that they already had a taste of French grammar, which has many similarities to ours, and also helped to avoid those accusations of cross-contamination. However, this year Jersey schools now start teaching French in Year 5, and as a result we have moved down a year to begin Jèrriais in Year 4 - this in effect means that for many pupils we are teaching them their first non-English (I am understandably loath to say foreign) language.

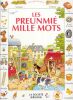

One of the difficulties that we face is that it is quite hard to get materials “off-the-shelf”, and so we are faced with producing almost everything in-house. We now have four textbooks, produced in full colour, associated workbooks, a CD-Rom, inspired again by the Isle of Man, and a phrasebook, which makes up in some way for the absence of a useable dictionary (the only one available is over 600 pages long, costs over £40 and is from Jèrriais to French!) We also produce a quarterly magazine entirely in Jèrriais, which is clearly aimed at native-speakers, but which includes content that we hope will draw our pupils in. This is going out to individuals, groups and societies in Jersey, as well as in France, Belgium and Switzerland. We have co-operated with Jersey's learned society, the Société Jersiaise, to produce Les Preunmié Mille Mots, using the template provided by the publishers Usbourne, and we are currently working on a book of Jersey history and legends.

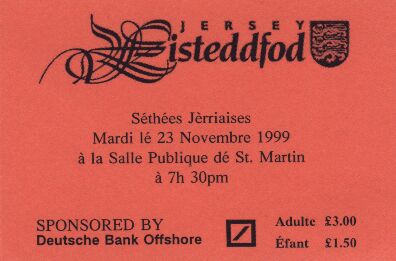

One of the difficulties that we face is that it is quite hard to get materials “off-the-shelf”, and so we are faced with producing almost everything in-house. We now have four textbooks, produced in full colour, associated workbooks, a CD-Rom, inspired again by the Isle of Man, and a phrasebook, which makes up in some way for the absence of a useable dictionary (the only one available is over 600 pages long, costs over £40 and is from Jèrriais to French!) We also produce a quarterly magazine entirely in Jèrriais, which is clearly aimed at native-speakers, but which includes content that we hope will draw our pupils in. This is going out to individuals, groups and societies in Jersey, as well as in France, Belgium and Switzerland. We have co-operated with Jersey's learned society, the Société Jersiaise, to produce Les Preunmié Mille Mots, using the template provided by the publishers Usbourne, and we are currently working on a book of Jersey history and legends. Our team consists of two full-time workers, my colleague Geraint Jennings, who is webmaster of our 2500 plus pages on the Internet, and myself and seven native-speakers who teach between one and three lessons per week. We are trying to find some new recruits! Children take part in the Jersey Eisteddfod, as part of a group singing Jèrriais songs in their first year, and in subsequent years performing prepared readings of poems in our language, they form a choir to sing at the Jèrriais Christmas carol service as well as busking for Jersey's Joint Christmas Appeal, and small groups also take part in the annual Fête Nouormande, which takes place in Jersey, Guernsey and in mainland Normandy in turn. We run a postcard project each year, in which children send cards to pupils from other Jèrriais classes, and some have gone on to maintain pen-friend relationships with their contacts, and earlier this year we had a competition to design a Christmas card, which has been professionally printed.

Our team consists of two full-time workers, my colleague Geraint Jennings, who is webmaster of our 2500 plus pages on the Internet, and myself and seven native-speakers who teach between one and three lessons per week. We are trying to find some new recruits! Children take part in the Jersey Eisteddfod, as part of a group singing Jèrriais songs in their first year, and in subsequent years performing prepared readings of poems in our language, they form a choir to sing at the Jèrriais Christmas carol service as well as busking for Jersey's Joint Christmas Appeal, and small groups also take part in the annual Fête Nouormande, which takes place in Jersey, Guernsey and in mainland Normandy in turn. We run a postcard project each year, in which children send cards to pupils from other Jèrriais classes, and some have gone on to maintain pen-friend relationships with their contacts, and earlier this year we had a competition to design a Christmas card, which has been professionally printed.For the first time we have 150-200 children learning to speak, read and enjoy Jèrriais. Will some of them be fired with enough enthusiasm for the language to bring up their own children as first-language Jèrriais speakers - neo-Jèrriais? or even better, to be the teachers of the future? Who knows ? - it has happened in the Isle of Man.

We have a saying in Jèrriais “Vielles amours et tisons brûlés sont deux feux bein vite ralleunmés” - old loves and burnt embers are fires which can be quickly re-ignited. Perhaps, just as we seemed to reach that point forecast by the nineteenth century pundits when they said English would extinguish all before it, the embers have started to glow more brightly….

Mèrcie bein des fais - Thank you