History Section

St. Cyr

Abreuvoir - A place for watering livestock

The Abreuvoir at St Cyr, St John, is a simple stone channel through which the stream has been diverted. Rights of usage were very important, especially to rural communities. Although Jersey is very fortunate to have many free flowing streams, the Courts were often asked to deliver judgements as to whether, or not, individual properties had the right to use a particular Abreuvoir.

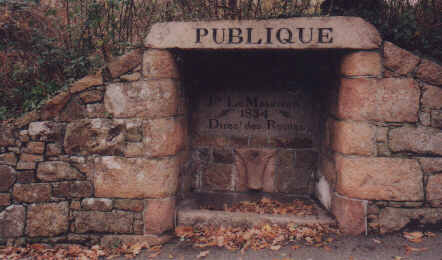

The St Cyr abreuvoir

The Abreuvoir at St Cyr was not a public Abreuvoir. It is situated at the end of the short private lane which also leads to the Lavoir. Not all Abreuvoir are as closely associated with an adjoining Lavoir, some stand alone and, thanks to our Victorian forefathers, many are elaborate and imposing structures.

Photographs of the following four examples give an indication of the variety to be seen:

La Botellerie, St Ouen, a simple catchment pond fed by its own spring.

Jubilee Hill, St Peter, an imposing granite structure with a separate basin for use by herdsmen, or other passers by.

La Marquanderie, St Brelade, with a beautifully carved head incorporated into the trough.

Le Marais à la Cocque, Grouville, an area which includes nearly all the elements one might expect to find when there is an abundant source of water.

Although functional, their modern day counterparts, discarded bathtubs, do not have the same charm.

The lavoir - Laundry

Court records bear witness to the importance that families attached to their right to use a lavoir. The St Cyr lavoir, in St John, is a particularly good example of what was, in reality, no more than an area where certain householders agreed to maintain a facility for the communal washing of clothes and linen. In the local patois lavoirs were known as "Douets à laver".

The St Cyr lavoir, which dates from before 1629, only acquired its present form when it was rebuilt in 1813. During the rebuilding, the initials of the eighteen owners of properties having the right to use the facilities were engraved onto a dated stone. This stone still forms part of a wall in the short lane leading down to the Lavoir and its associated Abreuvoir.

In the one hundred and ten years before it was rebuilt, the eighteen proprietors were involved in many Court cases, with claims and counterclaims as to their rights to use the Lavoir. The resulting judgements and agreements have resulted in considerable information being available about the site. Perhaps in desperation, the owner of the main house of St Cyr eventually built himself his own private Lavoir, just twenty feet away in his garden.

The lavoirs in Jersey vary greatly in date and style. Some, like the one at St Cyr, were shared by several well-to-do families and are well built and fairly elaborate. Others are less grand and at their simplest consist of a rough stone or two, appropriately placed in a stream.

There were a considerable number of Lavoirs in Jersey. Many still remain in various states of repair, but others are lost; some are only identifiable from written evidence and others by the recollection of people who remember a specific place being used for washing. One example recently came to light when the daughter of a former tenant of Ponterrin Mill, in St Saviour, was invited to view ongoing excavations. She was able to point out the stone on which her grandmother washed clothes until the 1920's.

Our forebears did not regard washing as a daily chore and wash days, particularly for bed linen, were in part dependant upon the seasons. It was, for instance, good practice to wash when the gorse was just coming into flower. The linen could then be spread over the gorse to dry, thereby acquiring the scent of fresh young flowers, a pleasing smell which transferred to the linen store.

Despite the grand rebuild of 1813, progress overtook the use of outdoor washing places and the St Cyr Lavoir fell into disuse. It is now no more than a quaint reminder of some of the disadvantages of living in the good old days.

Fourne à caux - The lime kiln

Fourne à caux - The lime kiln

We are told that, in Jersey, the use of lime kilns was uncommon until about 1800, prior to which all lime based products appear to have been imported.

Lime mortar was an essential requirement in the building of castles. Although it is known that lime kilns were constructed on site to meet the needs of castle builders there is no evidence of this having happened in Jersey.

Writing in 1559 Sir Hugh Pawlet, Governor of Jersey, requested eighty tons of lime, for fortifications. Other letters written in the 1560's, when the Royal castles in the Channel Islands were being modified and strengthened, refer to a lime kiln at Hurst Castle, Hampshire, which "hathe bennne newe buylded", and to the importation of lime from Hurst and from Normandy.

From the La Cloche records of 1650 it appears that the use of lime mortar, for domestic purposes, was not common as they note that many houses collapsed following the heavy and prolonged rains which had washed out the clay bonding used in their construction.

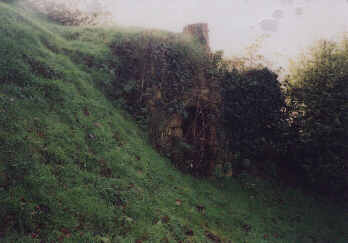

The lime kiln at St Cyr, which has been restored by the Société Jersiaise, is typical of the few surviving Jersey kilns and is built into a bank. This enabled the raw materials for the production of lime (alternate layers of fuel and sea shells) to be loaded from the upper level and the resulting lime raked out from an opening in the base of the kiln, at the bottom of the bank.

There is no natural occurrence of limestone in Jersey and, because of the expense, very little was imported to feed the kilns. Sea shells were the usual source material and, to supplement local supplies, shells were sometimes used as ballast in ships returning to the Island from England.

From the early nineteenth century the use of lime took on a new importance. Subject to various processes, it was also used as a soil conditioner, as lime wash in the cider apple orchards and as whitewash on the walls of buildings and stables. There is a kiln at Les Augrès, (the Zoo), which still has its slaking pit, formerly used for treating unprocessed lime.

The kilns were also used for burning seaweed, the ash of which was used for soil improvement. As lime was also used for this purpose could it be that thrifty Jerseymen used dried seaweed, in place of wood or peat, as a fuel source when burning shells for agricultural use?

See also: The Jersey Datestones Project: Lavoirs